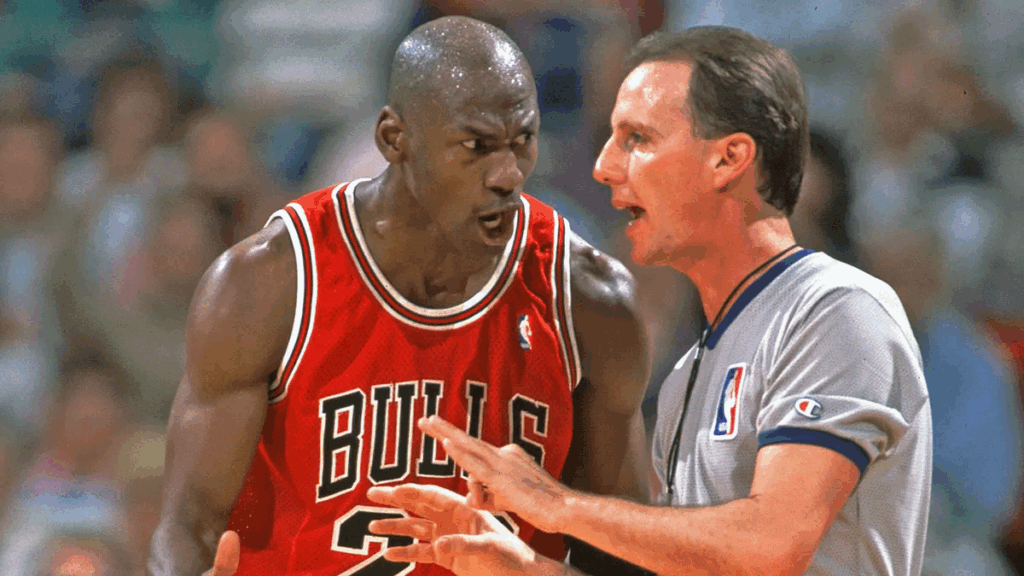

In an era defined by instant replay, referee pool reports, and transparent officiating standards, the debate over “star calls” remains persistent. This makes the stories from the old-school NBA, like those from “Bad Boy” Pistons legend John Salley, strikingly relevant.

Salley, who continues to provide sharp commentary on the league, once famously described playing Michael Jordan’s Bulls in the late 80s and early 90s as a fundamentally unfair proposition due to the officials’ devotion to the league’s rising star.

“I always said it was eight against five when you played against the Bulls because the referees were wearing Jordans. You know and they probably had tattoos of Michael on their chest,” Salley explained. “That’s what I remember them wanting their messiah to win.”

The “Subliminal Seduction” of Superstardom

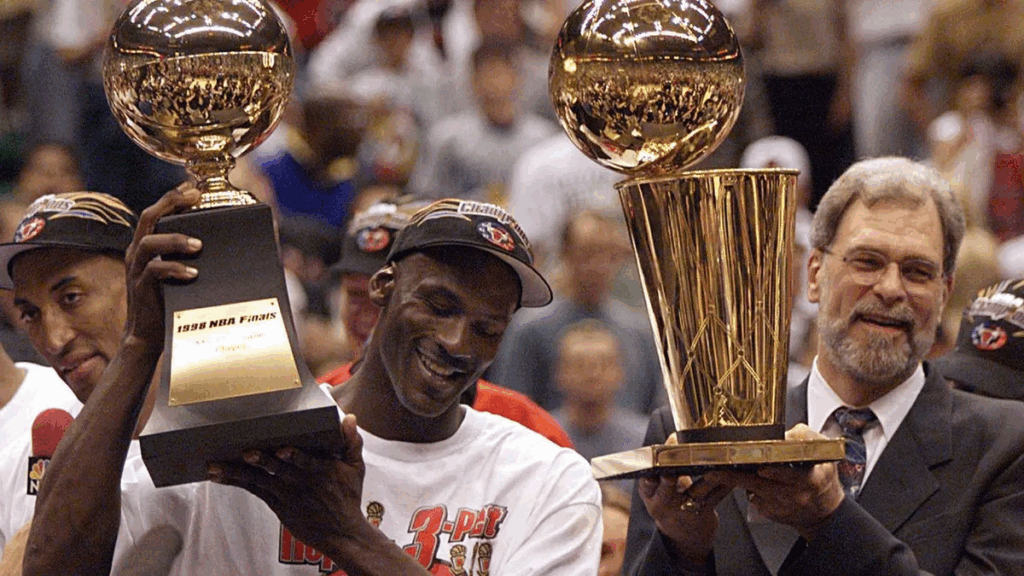

Salley’s comment points to something deeper than just bad calls: the immense, almost gravitational pull of superstardom on the game itself. He believes the bias was fostered not just by Jordan’s fame, but by the strategic marketing and psychological warfare waged by the Bulls organization.

Salley recalls how Bulls coach Phil Jackson leveraged media attention to label the Pistons as “dirty players,” creating a narrative that subconsciously influenced the whistle:

“It was subliminal seduction. He has everyone convinced. Michael Jordan has everyone convinced we’re dirty players,” which led to a policy shift that put the tough, physical Pistons under strict surveillance while the Bulls benefited from more foul shots.

The 2025 Star Call Parallel

In the 2025 NBA, the “star call” is still a central, frustrating topic for fans and players alike. While referees no longer wear a signature shoe named after a player, the league’s entire business model is built around elevating its biggest names.

This modern environment, even with its emphasis on transparency, still results in a palpable difference in how fouls are called on perimeter-oriented superstars versus role players. A player’s personal brand and media narrative have always influenced officiating, whether it was the rough-and-tumble perception of the “Bad Boys” or the polished, league-friendly image of the modern athlete.

Salley’s recollection serves as a crucial reminder: the struggle for objective officiating isn’t merely about correcting a missed hook or block; it’s about combating the ingrained human tendency to favor the person the entire league narrativeis built to protect. In the end, the NBA is an entertainment business, and protecting its heroes—its “messiahs”—has always been part of the game.